NOTE: I had mistakenly added a fixed effects vector on the model description. The results in table 4 show coefficients for a model without fixed effects. Aditionaly I should say that results from a zero-inflated model do not yield significantly different results. Sorry about that :P

Recently I was approached by one of Mexico's most popular sport websites, MedioTiempo.com with a question. Does football increase violence and criminal incidence? One of the things they wanted to know was if first division football ( Liga MX) games in Mexico altered the number of crimes commited in the home city of the playing team. Right away I though this was a really good question and started mindstorming about some possible ways to find out. This post is about one idea I had to test for this and the results I found. Hopefully a cooler and more visual post will come out soon at mediotiempo.com.

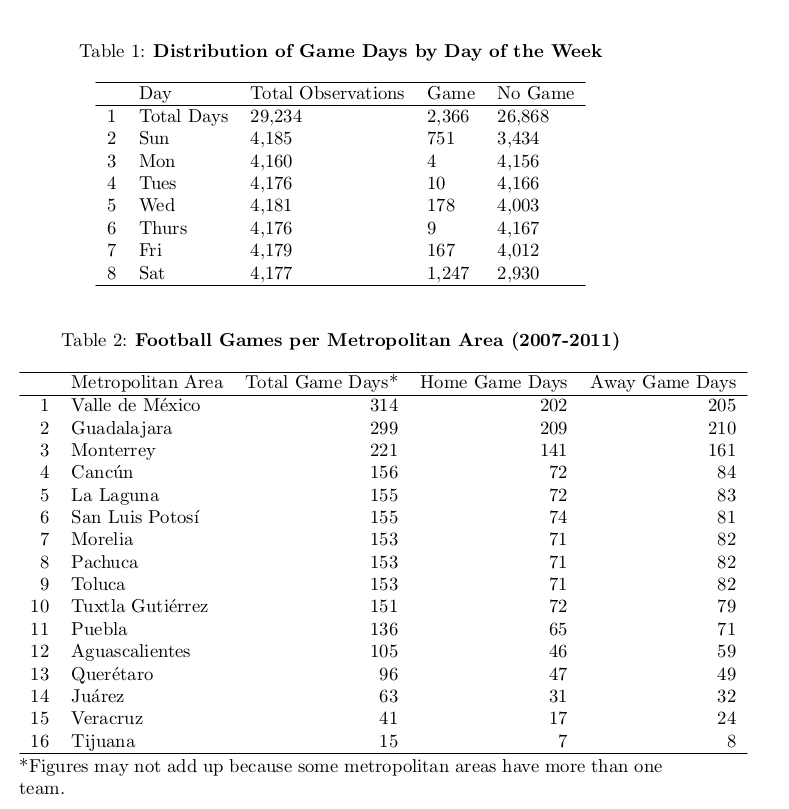

Due to the quality and availability of data the only way possible (that I could think of) was restricting the analysis to only include homicides, this mostly due to the fact that no criminal incidence data in Mexico is dissagregated to the daily level. I considered that the most useful dataset for this task was Mexico's mortality database (SINAIS) that is released yearly by INEGI. This dataset includes all registered deaths in Mexico since 1998 (and through 2011 as of september 2013) at the death certificate level. This allows for the creation of daily homicide counts for every city or metropolitan area with first division football. For the game data I scrapped several mexican sport websites that included information about the teams involved, the date, location and results of the game. I was able to compile the complete set of mexican first division football games for the years 2007-2013. After merging the two datasets the results was a 29,234 observations panel dataset that included homidice counts for every day between 2007 and 2011 for the 16 mexican cities that have had first division football teams in this period. Table 1 summarizes the number of observations by day of the week and if they had games or not. Table 2 shows the total number of game days for each of the metropolitan areas.

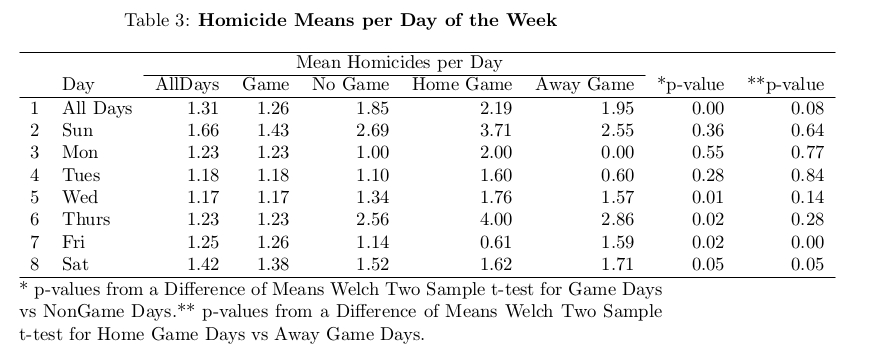

Firstly I ran a series of test of means to see if there was a significant difference in the number of homicides per metropolitan area on those days in which a local team played either home or away. It seemed that game days had on average 0.6 more homicides than non game days. Similar differences were found when analising different days of the week, where statistically significant differences were found for wednesdays, thursdays, fridays and saturdays. The results for the effect of Home vs Away games were less clear and in general it seems to suggest that the higher number of homicides are more directly related with the local team playing (regardless of location) than with the actual physical game happening within the metropolitan area. Table 3 shows these results.

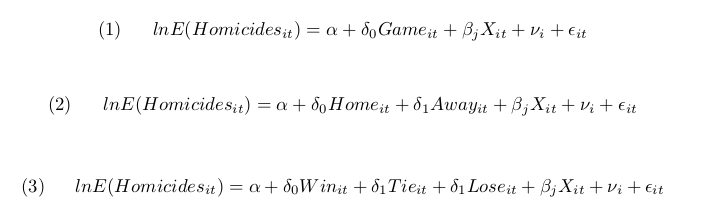

For the actual econometric model I decided to implement a negative binomial regression model similar to the one described by Cameron and Trivendi (1986), Grootendorst (2002) and used by Rees and Schnepel (2010). In this type of model the number of homicides reported depends on on whether a football game was played by the local team. The following equations describe the chosen econometric models:

Where Gameit is equal to 1 if a local team played, either home or away, on that day and is equal to 0 otherwise. For the second model, Homeit is equal to 1 if a local team played that home that day, Awayit is equal to 1 if the team played away. Finally for the third model, Winit equals one if the local team won its match that day, Tieit is 1 if the team tied and Loseit is 1 if the team lost. Where Xit represents the set of controls which include year, month, day of the week and national holiday. Finally exp(εit) follows a gamma distribution with a mean of 1 and a variance σ. Where if σ equals 0 then the model is reduced to a Poisson count model. Nevertheless the hypothesis σ = 0 was consistently rejected. This was most likely due to over dispersion of the dependent variable (homicides) and therefore a negative binomial model was employed instead of the more common Poisson model.

| Homicides | Homicides | Homicides | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | -0.77 (0.05)*** | -0.77 (0.05)*** | -0.76 (0.05)*** |

| Game (Yes) | 0.36 (0.05)*** | ||

| Home Game | 0.38 (0.06)*** | ||

| Away Game | 0.34 (0.06)*** | ||

| Win | 0.53 (0.09)*** | ||

| Tie | 0.41 (0.11)*** | ||

| Lose | 0.34 (0.12)** | ||

| AIC | 80858.16 | 80828.64 | 80858.92 |

| BIC | 81056.96 | 81035.71 | 81074.28 |

| Log Likelihood | -40405.08 | -40389.32 | -40403.46 |

| Deviance | 21806.34 | 21813.94 | 21809.31 |

| Num. obs. | 29234 | 29234 | 29234 |

| Notes: Estimated coefficients from a negative binomial regression model are reported. Standard errors are in parentheses. Although not shown, controls for day of the week, month, and year are included. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05 | |||

The model results seem to show that indeed football games are likely to increase the number of homicides within a metropolitan area. In fact the mere existence of game (either home or away) in which a local team is involved is associated with an enormous 43% increase in the number of homicides (e0.36=1.43). A very intuitive find is that the increase in homicides from a home game is higher than the effect of an away game, 46% vs 41% (e0.38=1.46 vs e0.34=1.41), nevertheless the difference is not as high as we would have thought. This should be a natural result when we think about stadium and post-stadium behavior of some of those who attend the games should easily account for a 5% increase than when the team plays aways from home.

But perhaps the most interesting find is that home wins are associated with much higher homicides increases (70%) than ties (51%) or loses (40%). It seems that when your team loses you are more likely to just go home and sleep it off and maybe when the local team wins you feel like going crazy.

The main conclusion here is that football games do matter in terms of violence and crime. Having found significant effects on homicide data it is very likely that these effects are also present for other types of crime such as assasult, vandalism, driving under the influence, public intoxication, etc. Hopefully in the future I'll be able to replicate this exercise using accidental deaths and manslaughter to test for possible effects.

Thanks for reading!!

PS: The code to replicate will be up on my github is available here.

PPS: I ran a wide load of robustness checks and model fit tests, you'll be able to see them on my code once it's on my github. Most alterations did not yield significantly different results or better model fits.